The CTO Playbook for Retail Transformation: Building for Agility, Data, and Customer Experience

In today’s retail environment, customer experience is the battleground—and technology is at the heart of it.

Prefer listening over reading? Press play and enjoy

When I first started out on my journey as a professional Software Craftsperson, one of the many books I read was “Growing Object Oriented Software Guided By Tests” by Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce. One of the things that really struck me was the notion that software is something that should be grown and nurtured over time. Just as we regularly tend to our plants and flowers to ensure they grow in the best way possible, we should continually nurture our software. In this article, I would like to explore why this is important, outline some tell-tale signs that your software is in decline, and some of the things that you can do to address it.

To start, let’s define what we mean by software rot. It may seem odd to refer to software as having the ability to rot. Of course, intellectually we know it doesn't really. Instead, what is referred to as software rot is a codebase becoming unwieldy due to unmanaged code complexity and improper design amongst other reasons. Complexity creeps in as “easy” code changes are made instead of the more difficult design changes required to support a change. Instead of teams identifying that their modelling is no longer fit for purpose and doesn’t support the demands being placed on it, they attempt to shoe-horn in new changes to fit the existing models. As a result, inappropriate coupling between components can be introduced (as components start to take on responsibilities they were not originally designed for) and complexity increases. It’s a well understood fact that the more complex a codebase is, the harder it is to change.

It’s also important to consider the wider environment and context in which our software is running. The technology landscape is constantly changing. A particularly good example of this is the proliferation of JavaScript frameworks over the past few years. As new technologies come and go, the communities built around them and the support and evolution of them also dwindle. If we’re not careful we can find ourselves running a particular framework or library that is no longer widely supported and actively worked on. This leaves us at the peril of any bugs in that framework or security risks that won’t be getting patched. It also means that we are likely to be falling behind as new libraries and frameworks are introduced that embrace new patterns, technologies, and even language features. If our software is simply standing still in this ever changing environment, that itself can lead to rot.

Now we have a common understanding of software rot, I’d like to outline some of the signs that might be indicative of software rot starting to set in. It is important to note that this section is referring to indicators only. That is to say, these signs will tell you have a problem but they won't necessarily tell you the underlying cause of the problem.

Fragility refers to software that tends to break in many places whenever a change is made, often even in areas that are conceptually unrelated to the change being made. As this increases, the software becomes very difficult to maintain because every new change introduces numerous new defects. In the best case, these defects are caught early by an automated testing suite. In the worst case they are found in production by end-users. This fragility can then lead to a loss of credibility for the software and the team owning it.

A particularly strong indicator of software rot is when a team starts to see the time taken to deliver value increasing. An ever increasing amount of time needed to add new features is a sign of code rigidity. This effectively means code that is difficult to change, more often than not because code is tightly coupled. For example, a new change causes a cascade of subsequent changes in dependent modules within the codebase. This results in teams often being fearful to address non-critical problems because they do not know the full impact of making one change, or how long that change will take.

Closely linked to the previous point, when a team starts to struggle to keep pace with the demands of the organisation that is also an indication that the codebase could be in an unhealthy state. For example, perhaps the domain model in the codebase is no longer a good fit and requires a new design in order to facilitate the needs of the business requirements. When a software team is unable to keep pace with the demands of the organisation there is a serious problem. It means that the organisation is at risk of losing any competitive edge it has in the market as it takes longer to ship new features to its customers.

It’s all well and good deploying your software to production frequently, but if these deployments result in breaking changes being introduced that impact your customer’s ability to use your product then that’s not good at all. We want to be deploying into production regularly, but not at the cost of quality. Change Failure Rate is a metric that was introduced by the DevOps Research and Assessment team (DORA) and is a measure of how often a deployment to production results in a failure of some kind being introduced. A high or increasing change failure rate suggests that our software is not as healthy as it should be and is likely missing adequate quality gates on the path to production. I wrote about Change Failure Rate in more detail as part of a previous article, which you can find here.

Software metrics are essentially measures of certain quality attributes of a codebase. It’s important to note that I’d advise against looking for absolute numbers across any of these attributes. Instead, it’s far more useful to focus on the trend over time. A decline tells us that our software has become less healthy in a certain area and we should take action to resolve it, to avoid software rot setting in.

There are a number of metrics that can be collected about a software codebase, the following list is therefore not exhaustive but a collection of those I have personally found useful in the teams I have worked with : Cyclomatic Complexity, Coupling and Test Coverage.

Often I hear teams using the number of lines of code (LOC) in a given method/file as a measure of complexity. This alone isn’t a good enough metric. For example, a small software program totalling 50 lines of code doesn’t sound overly complex. But if those 50 lines of code contained 25 lines of consecutive “if-then” code constructs then the code is actually extremely complex indeed! This is where Cyclomatic Complexity is a much better metric. It is a measure of the number of different paths or branches. Based on graph theory and developed by Thomas J. McCabe, it provides a quantitative measure of the number of linearly independent paths through the source code.

There are two categories of software component coupling. Firstly, Afferent Coupling. This refers to the number of classes in other packages that depend upon classes within a particular package. It is an indicator of the package's responsibility. The other category is Efferent Coupling. This is the number of classes in other packages that the classes in the package depend upon. This is an indicator of the package's dependence on externalities.outgoing. The higher the levels of coupling across both categories, then the harder the software code is to change. We want to strive for loosely coupled components as it increases flexibility, usability, and reduces the surface area for changes. In contrast, codebases with tightly coupled components tend to be more brittle and much harder to change and evolve over time.

Test Coverage is a measure of the amount of production code in a software codebase that has an automated test to exercise and assert against its behaviour. This metric is generally expressed as a percentage, i.e. a team may say “we have 70% test coverage.” As I outlined earlier in the article, I would always advise against looking for an absolute number with software metrics and this is especially true for test coverage. Instead favour looking at trends over time and relative test coverage measures between different parts of a codebase, particularly those that have changed recently. For example, if your team has made a high number of changes recently to an area of the codebase in order to support a new feature it would be alarming if the test coverage in that area had declined.

Technical Debt is a metaphor that was devised by Ward Cunningham, in 1992. He wrote:

“Shipping first time code is like going into debt. A little debt speeds development so long as it is paid back promptly with a rewrite... The danger occurs when the debt is not repaid. Every minute spent on not-quite-right code counts as interest on that debt. Entire engineering organizations can be brought to a stand-still under the debt load of an unconsolidated implementation, object-oriented or otherwise."

In other words, technical debt is when we prioritise quick delivery over code quality. In the short term, this is acceptable. However, if technical debt is not repaid on time, it can lead to software deterioration.

Developer Experience (DevEx) can also be a good indicator of software rot. Developers spend the majority of their time working within a codebase. If that codebase is difficult to work with then it’s going to affect their morale which can lead to the overall team morale declining too. Paying attention to developer happiness can actually tell you quite a lot about the state of the codebase(s) they work on. A codebase that developers enjoy working with is generally a sign of a healthy codebase. Afterall, no developer really enjoys working with a complex, highly coupled and fragile codebase.

As mentioned previously, if you experience any of these issues in your teams then I’d strongly encourage you to take a closer look at your team’s software codebase. Knowing that these problems are good indicators that our software is not in a healthy position is a good starting point. But that still doesn’t help us in understanding the true underlying cause(s). These indicators mentioned can also be thought of across two dimensions: leading indicators and lagging indicators. We ultimately need to dig deeper into the software to address the problem(s).

I used the analogy of plants and flowers earlier in this article to illustrate that software should grow continuously over time. Effectively we want our software codebases to support evolution and incremental change. Driving for this goal will encourage us to consider things like software complexity, testability, the appropriate coupling between components, and so on. One of the key things teams need to embrace is the continuous refactoring of their codebases. Whether it be removing unused ‘dead’ code, removing code duplication, or simplifying design models all of this helps to keep a codebase clean, minimise complexity and ultimately keep the cost of making changes low.

Testability in its most basic form is a measure of how easy it is to test a particular piece of software. It can also be expressed as the degree of likelihood that a test is likely to highlight a defect in the software. I have also heard people refer to testability as the likelihood that a test will be written! The theory, of course, is that if the software is hard to test then there’s a higher chance that it won’t happen. Testing is vitally important, particularly automated testing. Another thing I learned from reading Growing Object Oriented Software Guided By Tests, was that automated testing was just not about ensuring that the software behaved as we expected it to. It was also about designing our software. This is why Test Driven Development (TDD) is such a vital part of software development. By valuing testability and treating it as a first class citizen we allow for our software design to emerge gradually in an incremental manner. Each increment builds upon the previous one and builds out an automated test suite. This test suite then acts as a safety net for when we need to make changes. Often testability is thought of as an afterthought. But I’d very much encourage you to treat it as a first class concern.

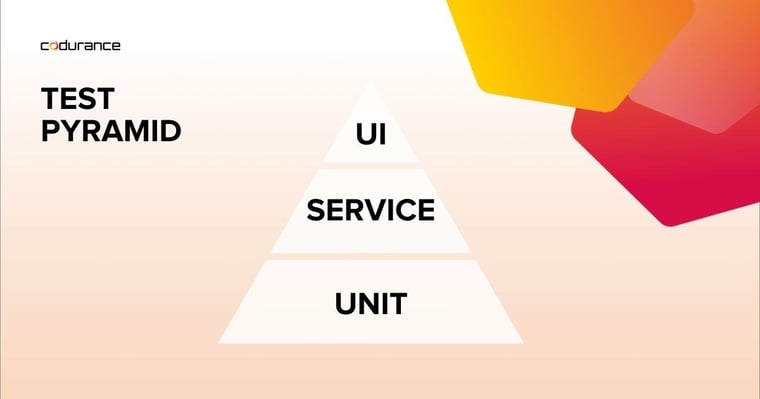

It’s also important to note that an automated test suite should comprise different types of tests that exercise various parts of the codebase. In his book Succeeding With Agile, Mike Cohn came up with the “Test Pyramid” concept. It is a nice visual guide to help teams think about different layers of testing. It also helps guide much testing to do at each of the layers, relative to each other. This is often a good starting point for teams to discuss what their automation test suite should look like. Ideally, a good automated test suite should comprise mostly of small unit tests that are quick to run and give us feedback that an individual component in isolation behaves as expected. But those tests alone are not sufficient so we need other types of tests that ensure that multiple components work together as expected. These tend to be a little slower as their scope is wider whilst they are important, there is generally less of them compared to unit tests. This ensures that the automated test suite provides a timely feedback loop. The image above shows a very basic example Test Pyramid, with the differing types of test at each level. It can be a useful exercise for teams to analyse their automation test suite and see whether they have a pyramid shape test breakdown or not. For example, I’ve seen teams that have had an inverse pyramid shape (i.e. many more UI end-to-end tests than service or unit level ones). This meant their test suite was slow to run and when these UI-driven tests did break, it was often difficult to reason why. Also, that team suffered from a number of production “edge-case” bugs as a result of a lack of individual unit tests around each component.

A key principle to keep in mind in software design is simplicity. The Extreme Programming (XP) community talks about Simple Design and phrases such as "Do the Simplest Thing that Could Possibly Work" and "You Aren't Going to Need It" (commonly referred to YAGNI). By striving for simplicity, we achieve two things - we allow our software to evolve incrementally over a series of small steps each building upon each other and containing just enough design to meet the requirements at that time. Secondly, we reduce complexity. The more complex a design is, the more difficult it is to reason about. It is also possible that we design with the future in mind and our predictions are incorrect. As a result, the complex we built isn’t actually fit for purpose and requires re-work, where we would have been much better off keeping it simple, to begin with.

Incremental change is the idea that changes that are required to be carried out on a software codebase are broken down into smaller chunks and applied in turn. Doing so means that we reduce the scope of each change and therefore the complexity and risk associated with it. We want our software codebases to be able to support this incremental change approach.

It’s important for a software development team to have a shared understanding of what ‘healthy’ means for their software. This is true for two reasons. Firstly, it ensures that all the team members are going to be pulling in the same direction but also it creates a social contract within the team, to keep the quality of the software and code high. A good way of doing this is through a set of common guidelines and principles that the team comes up with together. If the team chooses to, these can then be codified in the form of automated linting rules, thresholds for codebase metrics and others. When this is done well, a codebase should look and feel as though it has been written by the same person. All too often, team members have differing opinions of design and code styles and these differing opinions are expressed in the code. For example, a multitude of patterns to achieve similar things, inconsistent naming or a lack of clear codebase structure. All of these things introduce accidental complexity to a codebase and can make it harder to change over time.

In the book Extreme Programming Explained, Kent Beck refers to Agile software development as being akin to driving a car.

“We use driving as a metaphor for developing software. Driving is not about pointing the car in one direction and holding to it; driving is about making lots of little course corrections.”

Whilst the metaphor was used in the book to primarily talk about the act of planning within Agile software development projects, I think the metaphor also holds true for software design. I see the act of refactoring as the course corrections Kent Beck refers to and by doing this refactoring often, we can keep each one small so that we are making lots of little course corrections. Each of these refactors, whilst not changing the functionality of the software plays a vital role. It refines the software a little each time to match some new understanding we have about the world and keep the code manageable.

If we find ourselves in a position where we have to tackle large-scale refactorings it’s generally a sign that we’ve not been doing the small and often refactoring. As a result, our software design has drifted out of sync with the real world domain model and now a new requirement has come along that no longer fits the model we have in our software. Alternatively, large-scale refactorings can be a sign of high complexity in an area of the codebase that has developed over time and has reached a point that the team can no longer effectively add changes in that area of the code.

In the context of software development, Information Radiators are visual displays that present some insight into the current state of the software. These are usually displayed on large monitors within the team space and present information like the current state of the software build, overview of the automated test suite, software metrics and so on. These are displayed in a highly visible location so they are not only visible for the software team but also for wider stakeholders within the organisation that enter the team-space. By using Information Radiators, teams are openly showing the health of their software and by doing so it helps to magnify any potential issues with software health that may arise. If the automated test suite, for example, starts to have a failure, this should be highly visible on a monitor so much so that it is hard to ignore and prompts immediate action, which is one of the key aspects of this. By adopting Information Radiators, it promotes a culture of transparency - the team is saying that they have nothing to hide from visitors and stakeholders. But perhaps more importantly, it also conveys within the team it has nothing to hide from itself and will acknowledge any issues and problems that arise head-on as opposed to burying them.

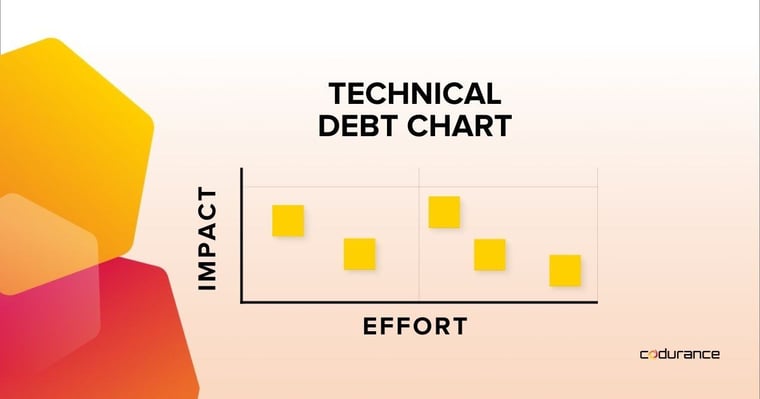

A good example of an Information Radiator that I’ve seen many teams adopt is a “Technical Debt Chart.” This is usually placed on a wall within the team space and is a chart where the team members place cards detailing technical debt items. The cards are placed at appropriate items based on two-axis: effort and impact. Doing so helps to give a quick indication of the type of technical debt the team has and the sheer amount but also makes it very visible. Team members then meet regularly and gather around the chart to discuss the items. This is important for two reasons - firstly to check if the cards are still placed in the correct position according to effort and impact. It is important to note that as the codebase evolves some technical debt items may require more effort to resolve. Also, the team might be aware of the need to change a particular area of the codebase where there is some outstanding technical debt. In which case, paying back this technical debt now will likely have a big impact as it could speed up the development of these new changes.

This article has attempted to raise awareness of software rot by putting together a definition of what it means, some indicators to watch out for and finally some things to arm yourself with in order to address software rot. If you’re reading this article about to embark on building a new piece of software, you might think that software rot isn’t something you need to consider. I’d caution against that. By embracing the theory of Evolutionary Architecture upfront, your team can be on the front-foot to guard against and minimise software rot setting in. The combination of appropriate coupling and supporting incremental change will ensure your codebase complexity is low. Putting in place automated detection mechanisms such as codebase metrics and automated tests will allow you to quickly spot when your codebase is starting to drift off course and allow you to take appropriate action early to minimise the impact of any software rot. It is also important to understand that it’s vital to continually nurture and evolve our software codebases. In an ever-changing world, software that stands still will naturally rot as the technology landscape and customer expectations rapidly change. Although authored back in 1974, Lehman’s laws of software evolution, particularly the first two are still very relevant today: “a system must be continually adapted or it becomes progressively less satisfactory”, “as a system evolves, its complexity increases unless work is done to maintain or reduce it”.

To recap, here is a breakdown of the indicators of software rot to watch out for and some of the ways to address them:

Indicators of Software Rot:

Ways to Address Software Rot:

In today’s retail environment, customer experience is the battleground—and technology is at the heart of it.

Many software teams face a common challenge: they inherit large, complex systems built long before they arrived. Over time, these systems accumulate..

When faced with the challenge of modernising legacy systems in businesses, we know the potential benefits are immense, but so are the challenges...

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies