- By Javier Chacana

- ·

- Posted 30 Sep 2021

JBCNConf in times of COVID

This year, the 2021 edition of the traditional JBCNConf was held. Unfortunately, the 2020 event didn't take place the year prior due to difficulties..

We already spoke about the different type systems and how they work here, now it's time to write some code and see how type can help us.

Imagine that we are building a company that searches for flights on multiple websites. We are exposing an endpoint that accepts JSON. Right now we are only dealing with simple searches where all flights will have a return and the accepted JSON is:

{

"startDate": "10/11/2019",

"endDate": "15/11/2019",

"origin": "LHR",

"dest": "DUB"

}

Now that we receive that request, we have to understand what composes a search:

We can have all those validations without creating a class. Imagine that we have a controller that will receive that, parse the JSON, and send to a service.

The code for the application is:

public class FlightSearchController {

private SearchService searchService;

public FlightSearchController(SearchService searchService) {

this.searchService = searchService;

}

public List<Flight> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

JsonObject searchObject = parseJson(searchRequest);

return searchService.findFlights(

searchObject.get("startDate").asText(),

searchObject.get("endDate").asText(),

searchObject.get("origin").asText(),

searchObject.get("dest").asText());

}

}

class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(String startDate, String endDate, String origin, String dest) {

return searchRepository.findFlights(startDate, endDate, origin, dest);

}

}

class SearchRepository {

public List<Flight> findFlights(String startDate, String endDate, String origin, String dest) {

// implementation

}

}

There are so many smells in that snippet that made me sick. Jokes aside we have to see that we are moving all the validations to the edge of the application, this will only blow up when we make a database call with invalid parameters. This might be a problem for error handling because we want to tell the person that called the API which kind of error is, a database problem would usually be a 5XX, but in reality, could be a 4XX since the problem is in the payload that was sent, not in the database.

There are two types of validations that have to be done in this part:

Let's start with the dates, there are not multiple date formats and isn't a problem that we face frequently. Parsing the startDate and endDate parameters to LocalDate in the SearchService will help us to always have a valid date when searching in the database. In case an invalid date is sent a DateTimeException exception will be thrown, which makes easier to identify that is a problem with the data and not the database.

class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(String startDate, String endDate, String origin, String dest) {

LocalDate flightStartDate = parseDate(startDate);

LocalDate flightEndDate = parseDate(endDate);

return searchRepository.findFlights(flightStartDate, flightEndDate, origin, dest);

}

}

class SearchRepository {

public List<Flight> findFlights(LocalDate startDate, LocalDate endDate, String origin, String dest) {

// implementation

}

}

class DateTimeFormatter {

private static LocalDate parseDate(String date) {

DateTimeFormatter formatter = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("dd/MM/yyyy");

return LocalDate.parse(date, formatter);

}

}

Now with the parser being done in the service we replace exceptions related to our database for DateTimeParseException, this makes it way easier to capture the right exception instead of trying to figure it out what was happening. What we have now is better than the previous code using strings all around but we can and must do better. The SearchService is throwing DateTimeParseException and we can handle that case in the controller and return something like 400 - Bad Request.

Now let's take care of the IATA, the IATA specification (source: Wikipedia, I didn't read the specification) says that's a code composed by three letters. In this case, we can create a class for it and add the validation.

class InvalidIATAException extends InvalidArgumentException {}

class IATA {

public final String iata;

public IATA(String iata) {

if (iata.length() != 3) {

throw new InvalidIATAException();

}

this.iata = iata;

}

}

Then we change the service and the repository to start using types:

class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(String startDate, String endDate, String origin, String dest) {

LocalDate flightStartDate = parseDate(startDate);

LocalDate flightEndDate = parseDate(endDate);

IATA originAirport = new IATA(origin);

IATA destAirport = new IATA(dest);

return searchRepository.findFlights(flightStartDate, flightEndDate, origin, dest);

}

}

class SearchRepository {

public List<Flight> findFlights(LocalDate startDate, LocalDate endDate, IATA origin, IATA dest) {

// implementation

}

}

With those changes, we can at least guarantee that the dates passed to the database are valid and the formatting doesn't matter much at this point now because it's encapsulated inside of a class. We can't confirm that the date exists in the database but there won't be any exceptions thrown when the query is executed.

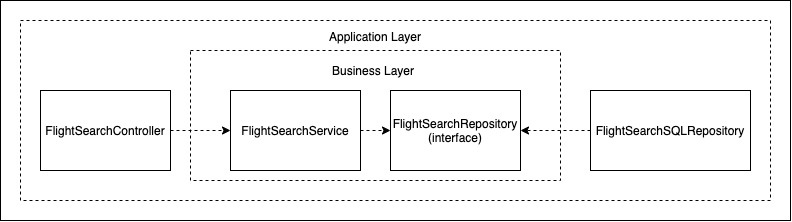

Just a clarification, The Application Layer is the part that handles the communication, in this case, it would be the controller. The controller isn't related to the business but just a way of input/output for our domain. This diagram shows the boundaries between them:

We use types, dependency injection and interfaces to abstract what the application is doing. The FlightSearchService doesn't care if the data is coming through HTTP, RPC or even a CLI. The same goes for the FlightSearchRepository, it just cares that you can store and retrieve the data later, the how doesn't matter for the business, that's an application responsibility.

Continuing with the changes. The problem with the codebase is that it's being filled with application code that isn't relevant. The solution for that is moving that code up the application layer.

class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(LocalDate startDate, LocalDate endDate, IATA origin, IATA dest) {

return searchRepository.findFlights(flightStartDate, flightEndDate, origin, dest);

}

}

public class FlightSearchController {

private SearchService searchService;

public FlightSearchController(SearchService searchService) {

this.searchService = searchService;

}

public ResponseEntity<List<Flight>> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

JsonObject searchObject = parseJson(searchRequest);

try {

LocalDate flightStartDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("startDate").asText());

LocalDate flightEndDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("endDate").asText());

IATA originAirport = new IATA(searchObject.get("origin").asText());

IATA destAirport = new IATA(searchObject.get("dest").asText());

} catch (DateTimeParseException | InvalidIATAException e) {

return ResponseEntity.status(400).build();

}

var flights = searchService.findFlights(flightStartDate, flightEndDate, originAirport, destAirport);

return ResponseEntity.body(flights).build();

}

}

Now the SearchService is free from any code that isn't related to our business domain, if you want to test you will not have to worry about passing things that will be parsed to the proper classes and testing if the parsing is working, if you create anything else than a LocalDate compiler will tell you and if the parsing of the string to the LocalDate type fails you get an exception even before calling the service.

All those things that I've said here aren't made up shit that I'm coming to try to look smart, they are code smells that many other people have written about before. The name of the code smell that we just changed is Primitive Obsession, it's a code smell were you use primitive types to deal with things that should be abstracted as an object.

We already mentioned the Domain and the Application layer, where should we be adding the validation for the values that we have. For things like parsing dates or a JSON which is explicit out of the business domain, it's better to make them live inside the Application Layer so we can test the Business Layer without having to worry about that, also the way we drive the application might be different depending on what you want. That isn't something that our Business should be worried about.

Let's start work on that to add some more types and safety to our search. Remember what I said at the beginning about not being able to hold too many things in my memory? We have this problem here, we have the business concept of search parameters but in the code, this isn't mentioned at all. When you talk to someone that isn't a developer they will say about the search parameter and you have to associate that to a specific group of fields and rules that are distributed around the codebase.

What happens if we add another field? You have to memorize that but what if you were on holidays when they did that change, you probably are going to have conversations were your knowledge is out of date. It's possible to fix that using types to abstract the complexity and defer the need to know certain information to the last second.

Let's start refactoring our code, the first thing we can change are the dates, we always need a start date and an end date. Passing them around would be easier if they were always together wouldn't?

public class DateRange {

final LocalDate start;

final LocalDate end;

public DateRange(LocalDate start, LocalDate end) {

this.start = start;

this.end = end;

}

}

public class FlightSearchController {

//...

public ResponseEntity<List<Flight>> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

JsonObject searchObject = parseJson(searchRequest);

try {

LocalDate flightStartDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("startDate").asText());

LocalDate flightEndDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("endDate").asText());

DateRange dateRange = new DateRange(flightStartDate, flightEndDate);

IATA originAirport = new IATA(searchObject.get("origin").asText());

IATA destAirport = new IATA(searchObject.get("dest").asText());

} catch (DateTimeParseException | InvalidIATAException e) {

return ResponseEntity.status(400).build();

}

//...

}

}

public class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(DateRange dateRange, IATA origin, IATA dest) {

return searchRepository.findFlights(dateRange.start, dateRange.end, origin, dest);

}

}

We can go even further and add some kind of validation in the date range because we don't want the start date to be after the end date, this could cause all sorts of problems.

public class IllegalDateRange extends InvalidArgumentException {}

public class DateRange {

final LocalDate start;

final LocalDate end;

public DateRange(LocalDate start, LocalDate end) {

if (start.isAfter(end)) {

throw new IllegalDateRange();

}

this.start = start;

this.end = end;

}

}

Now it's way harder to represent an invalid date range in the system (not impossible tho).

Now we just need a final type for our search with all those fields that we are passing around.

public class SearchParameters {

final DateRange dateRange;

final IATA origin;

final IATA destination;

public SearchParameters(DateRange dateRange, IATA origin, IATA destination) {

this.dateRange = dateRange;

this.origin = origin;

this.destination = destination;

}

}

public class FlightSearchController {

//...

public ResponseEntity<List<Flight>> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

JsonObject searchObject = parseJson(searchRequest);

try {

LocalDate flightStartDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("startDate").asText());

LocalDate flightEndDate = parseDate(searchObject.get("endDate").asText());

DateRange dateRange = new DateRange(flightStartDate, flightEndDate);

IATA origin = new IATA(searchObject.get("origin").asText());

IATA destination = new IATA(searchObject.get("dest").asText());

SearchParameters searchParameters = new SearchParameters(dateRange, origin, destination);

} catch (DateTimeParseException | InvalidIATAException e) {

return ResponseEntity.status(400).build();

}

var flights = searchService.findFlights(searchParameters);

return ResponseEntity.body(flights).build();

}

}

public class SearchService {

public List<Flight> findFlights(SearchParameters searchParameters) {

return searchRepository.findFlights(searchParameters);

}

}

class SearchRepository {

public List<Flight> findFlights(SearchParameters searchParameters) {

// implementation

}

}

All those changes that were made focused in removing a code smell called Data Clumps.

Everyone is a close friend of nulls, from bankrupting companies to making devs drink under their desks, they are everywhere. Inevitable like making bad decisions when you are drunk, we need to deal with nulls.

Is null a type or the lack of types? With that philosophical question that doesn't matter, sometimes we need to represent that a call don't have anything to return. When getting an environment variable, for example, that variable might not be declared and we represent that as a null.

This is not a problem, what can cause harm is the fact that the null might not be noticed or dealt before the values are used.

For example:

public class NullExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String home = System.getenv("HOME");

System.out.println(home.length());

}

}

This snippet will throw a NullPointerException but at any moment we were warned that the method would return null, we might know for reading the documentation or the code. We can add a null check before calling home.length(), that solves the problem of the exception that we are getting, we still have the problem that we have to do that after every call of the method, and human beings are unreliable to do repetitive tasks like that. Do you know who is good checking that kind of stuff? The compiler of course.

With all the advances in modern society and Java, there's a quite decent way of dealing with this problem. Java provides us with the Optional<> that can wrap null values for us. The main advantage of using an Optional is that we can't use the value straight away (please, don't call .get() straight away), we explicitly have to deal with the possibility of a null value. This is way better than returning null or just throwing an exception. The final result would be:

public class OptionalExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Optional<String> home = Optional.ofNullable(getenv("HOME"));

home.ifPresent(System.out::println);

}

}

You can use Optional to represent when a query doesn't have any result like in our flight search system. The optional is used to represent the fact that a flight number does not exist.

class SearchRepository {

public Optional<Flight> flightById(FlightId id) {

// implementation

}

}

Optional does the work when we have to represent that a function might return a null value. What if we need to ensure that all parameters are valid, how do we do that?

Sometimes we are limited by what our tools can do, when this happens means that we have to do the extra work to compensate that or to get better tools, in this case, we have Kotlin, which comes with Non-Nullable types and some other nice tricks.

Before starting talking about Kotlin, I want to make clear that if you are using Java properly and taking care with what you call you are not going to have too many NullPointerException problems, the best way is to know the language API and the libraries you work with.

One of the main features of Kotlin is the fact that regular types can't be null. You can't assign null to a value, neither return null from a function UNLESS you use a Nullable type, which is different.

Back to our search application, imagine that we were using Kotlin since the beginning, the DateRange class would be something like this:

data class DateRange(val start: LocalDate, val end: LocalDate)

Now we have new requirements, we need to start to sell one round trip, this means that we will only have the start for the date range. In Kotlin this would translate to:

data class DateRange(val start: LocalDate, val end: LocalDate?)

The difference seems minimal but the ? in the end field change how we use the field. A Nullable Type in Kotlin would the equivalent of an Optional in Java with the difference that in the start the compiler will not allow null values.

data class DateRange(val start: LocalDate, val end: LocalDate?)

fun main() {

println(DateRange(LocalDate.now(), LocalDate.now())) // DateRange(start=2020-01-26, end=2020-01-26)

println(DateRange(LocalDate.now(), null)) // DateRange(start=2020-01-26, end=null)

println(DateRange(null, LocalDate.now())) // Does not compile

}

With that, we can truly enforce that we are not passing null values as parameters for our functions.

when keywordWe already spoke about exceptions and where to put them. The things is: Exceptions are quite abruptly and violent. You don't return exceptions, you throw them at the face of the method that called you, and to add insult to the injury you print a really long stack trace to be sure that the person sees what you just did.

Drama and pettiness aside exceptions are not explicit and in the case of unchecked exceptions, it's really hard to keep track of them all. They are used as a way to express when something goes wrong with your system and that's why they look different from the regular flow validations and returning certain invalid states are in many cases represented as exceptions. In a language like Java, that's the convention and there are not many tools that help to overcome that.

Going back to our company, we have to add business validation now. The origin can't be the same one as the destination, if this happens we have to return the status code 412.

public class OriginAndSourceEqualsException extends Exception {}

public class FlightSearchController {

//...

public ResponseEntity<List<Flight>> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

//...

try {

var flights = searchService.findFlights(searchParameters);

} catch (OriginAndSourceEqualsException e) {

return ResponseEntity.status(412).build();

}

return ResponseEntity.body(flights).build();

}

}

This code doesn't look too bad, but what if we start do add more validations with different status code? we are going to have to add more and more catch clauses, if we have to implement the catch in multiple places, how can we be sure that we are not forgetting anything? In Java, the compiler doesn't do exhaustive checks. This is when we use Sealed Classes and the when clause.

Sealed Class is a construct that allows you to create restricted hierarchies, other people will not be able to extend from the outside of sealed classes. They are like a powerful version of an Enum, we can use a sealed class to represent the result of our search.

class SearchResult {

class Success(val flights: List<Flight>)

class Invalid(val message: String)

}

class FlightSearchController {

//...

ResponseEntity<List<Flight>> searchFlights(String searchRequest) {

//...

val result = searchService.findFlights(searchParameters);

return when(result) {

is SearchResult.Success -> ResponseEntity.body(result.flights).build()

is SearchResult.Invalid -> ResponseEntity.status(412).build()

}

}

}

Combined with the keyword when the Kotlin compiler forces you to check all the possibilities for the sealed class or to be a generic else that take cares of the parent sealed class.

Something that all the code snippets above has is that they all use final or val, that's because we want to make the fields immutable and avoid the mutation of the internal state in an object, exposing setters and allowing people to change the value of the fields can cause our objects to break, instead of that if we are using Immutable Types you have to instantiate a new class going through the validations again. Search about Value Objects if you want to know more about that.

In case you need to mutate the state of the object you have to follow some principles like Tell Don't Ask and good principles of OO, the main thing is to avoid exposing the internal of a class, a good example is adding to a list, never expose the list so people can add items to it, instead provide a method to add to the list.

// Bad

items.getList().add(item)

// Good

items.add(item)

You should also search for the methods of your language that are immutable, like in Java the Instant method is immutable but LocalDate doesn't.

During the examples, there were also many constructors with validations and more code than the usual, if you are doing that a lot you should totally learn about Static Factories that are mentioned in Effective Java, it will teach you how to write more idiomatic constructors for your classes.

There's also Inline classes, that's something that is coming to the next version of Kotlin and to some future version in Java. When you need to wrap a single value like an Id. I will not give any examples but you can check those two sources for Kotlin and Java.

This year, the 2021 edition of the traditional JBCNConf was held. Unfortunately, the 2020 event didn't take place the year prior due to difficulties..

Integration tests can be slow and unreliable because they depend on too many components in the system. Up to a certain point, this is unavoidable:..

This article is an account of how I learned to apply patterns. It condenses concepts from the first two weeks of the apprenticeship program by making..

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies