- By Javier Martínez

- ·

- Posted 10 Aug 2021

Functional patterns

Welcome pythonistas! In our last video session on design patterns we focused exclusively on patterns for the object oriented paradigm (OOP). To some..

If you are interested in functional programming as many of our craftspeople are, you will have heard talk about tail recursion. Tail recursion refers to a recursive function call that has been made from tail position. When a function call is in tail position it means there are no more instructions between the return of control from the called function and the return statement of the calling function. We will illustrate this with some code examples but first, why is it a big deal?

In 1977 Guy L. Steele submitted a paper to the ACM in which he summarised the debate over GOTO and Structured Programming, and he observed that procedure calls in the tail position of a routine can be best treated as a direct transfer of control to the called procedure. This, he argued, would eliminate the unnecessary stack manipulation operations that had led people to the artificial perception that GOTO was more efficient than procedure calls.

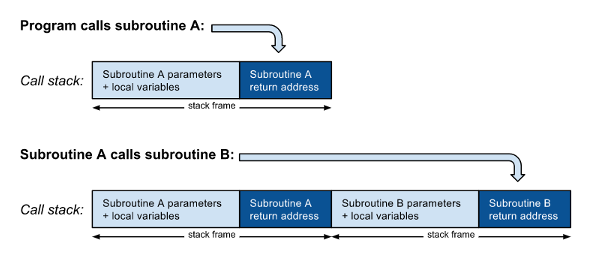

At the most basic level, a function or a procedure is a subroutine, called by a jump instruction to the subroutine entry point. What distinguishes a subroutine from a simple jump is that the calling code must first push the return address (the address of the next instruction to be executed after the subroutine returns) on the call stack before jumping to the subroutine. The subroutine parameters and local variables are also stored on a stack, which may be the call stack or a separate one:

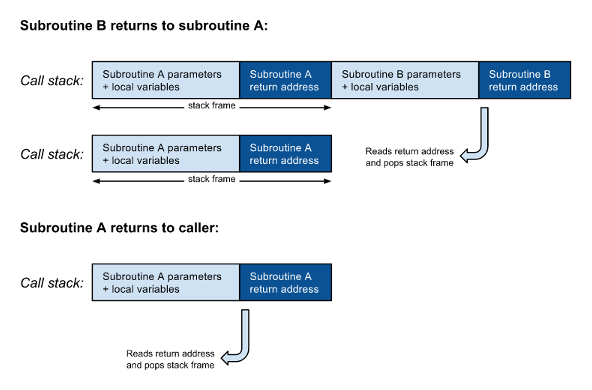

As shown in figure 1, when a subroutine A calls another subroutine B, a new stack frame including the return address must be pushed on the call stack on top of the return address from A. When B finishes, it reads the return address, pops its stack frame from the call stack, and returns to its caller A. When subroutine A finishes it does a similar thing:

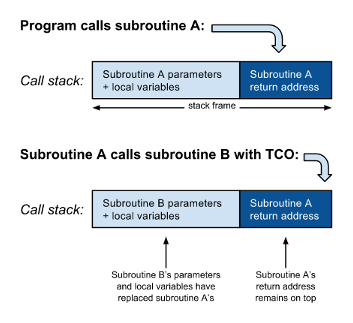

However, when the call to routine B is in tail position there are no more instructions between the return of control from B and the return statement of A. In other words, the program will return from B only to return immediately to the caller of A. There is therefore no need to push the return address from B on the call stack: the program can simply jump to B and when it completes, it will read the return address of A from the call stack and return directly to the caller of A. Furthermore, there will no longer any use for A’s local variables or parameters, so these can be replaced by the parameters and local variables for B:

A subroutine call in tail position can thus be optimised effectively by replacing it with a jump instruction. For this reason, tail call optimisation is also called tail call elimination. This is important because every time a recursive subroutine calls itself without TCO, it requires more space for the stack. A recursive program always runs a danger of running out of space that is not faced by an equivalent non-recursive program. This particularly matters to programs written in a functional style.

When we program in imperative style, recursion is a tool that we can use when the nature of the problem suits it; we are mindful of the memory requirements and take steps to avoid blowing the stack. The problem assumes a new dimension in functional programming because recursion is the method of choice to implement iteration. An imperative program may be able to iterate a loop ten million times quite happily. It would be completely unacceptable for a functional program not to be able to perform the same computation. Tail call optimisation allows us to write recursive programs that do not grow the stack like this. When Guy Steele developed Scheme with Gerald Jay Sussman, they made it a requirement in the language definition that TCO must be implemented by the compiler. Unfortunately, this is not true of all functional languages.

Consider this contrived example of a tail recursive program in Java:

int sumReduce(List<Integer> integers, int accumulator) {

if (integers.isEmpty())

return accumulator;

int first = integers.get(0);

List<Integer> rest = integers.stream().skip(1).collect(toList());

return sumReduce(rest, accumulator + first);

}

The recursive call to sumReduce is said to be in tail position because once it has been evaluated there is nothing more to be done in the outer call but return the value. With the default JVM memory settings, this routine throws a stack overflow error when called with a list of merely ten thousand integers.

To illustrate the way some functional languages get around this problem, let us rewrite the sumReduce function in Clojure:

(defn sum-reduce [integers accumulator]

(if (empty? integers)

accumulator

(let [[first & rest] integers]

(sum-reduce rest (+ accumulator first)))))

Writing Clojure like this in real life is not advised; the same thing can be better accomplished by (reduce + integers) but we will ignore that for discussion’s sake. The sum-reduce function exhibits exactly the same problem as its Java counterpart:

user=> (sum-reduce (range 1 10000) 0)

StackOverflowError clojure.lang.ChunkedCons.next (ChunkedCons.java:41)

To get around this problem Clojure provides the (loop (recur)) form:

(defn sum-reduce [integers]

(loop [[first & rest] integers, accumulator 0]

(if (nil? first)

accumulator

(recur rest (+ first accumulator)))))

Now the function is quite capable of summing ten million integers and more (although reduce is still faster):

user=> (sum-reduce (range 1 10000000))

49999995000000

But this is not tail call optimisation. The Clojure documentation describes loop-recur as “a hack so that something like tail-recursive-optimization works in clojure.” This suggests that tail call optimisation is not available in the JVM, otherwise loop-recur would not be needed. Unfortunately this is indeed the case.

Returning to the discussion we began with, the important distinction with TCO is that go to is more general than a loop construct; it can also optimise mutual recursion. This is not possible by transforming tail recursion into a loop. To illustrate with a non-trivial example, consider this Clojure solution of the popular bowling game kata:

(declare sum-up-score)

(defn sum-next [n rolls]

(reduce + (take n rolls)))

(defn last? [frame]

(= frame 10))

(defn score-no-mark [rolls frame accumulated-score]

(sum-up-score

(drop 2 rolls)

(inc frame)

(+ accumulated-score (sum-next 2 rolls))))

(defn score-spare [rolls frame accumulated-score]

(sum-up-score

(drop 2 rolls)

(inc frame)

(+ accumulated-score (sum-next 3 rolls))))

(defn score-strike [rolls frame accumulated-score]

(if (last? frame)

(+ accumulated-score (sum-next 3 rolls))

(sum-up-score

(rest rolls)

(inc frame)

(+ accumulated-score (sum-next 3 rolls)))))

(defn spare? [rolls]

(= 10 (sum-next 2 rolls)))

(defn strike? [rolls]

(= 10 (first rolls)))

(defn game-over? [frame]

(> frame 10))

(defn sum-up-score

([rolls]

(sum-up-score rolls 1 0))

([rolls frame accumulated-score]

(if (game-over? frame)

accumulated-score

(cond

(strike? rolls) (score-strike rolls frame accumulated-score)

(spare? rolls) (score-spare rolls frame accumulated-score)

:else (score-no-mark rolls frame accumulated-score)))))

This program is mutually recursive: sum-up-score calls score-strike, score-spare and score-no-mark, and each of these three call back to sum-up-score. The forward references to sum-up-score make it necessary to declare it at the beginning. All of the calls are in tail position and would therefore be candidates for TCO - would that the JVM could do it - but it is not possible to make use of loop-recur.

In this video, Java language and library architect Brian Goetz explains the historical reason why the JVM did not support tail recursion: certain security-sensitive methods depended on counting stack frames between JDK library code and calling code in order to figure out who was calling them. TCO would have interfered with this. He adds that this code has now been replaced and that support for tail recursion is on the backlog, albeit not very high priority. With the increasing interest in functional programming, and particularly the growth of functional languages that run on the JVM such as Clojure and Scala, the case for TCO support in the JVM is growing.

Welcome pythonistas! In our last video session on design patterns we focused exclusively on patterns for the object oriented paradigm (OOP). To some..

Solving a simple problem in Elixir In this article, I am going to solve the Word Count problem from Exercism in Elixir. I'll start with a form that..

Crafting web apps using finite state machines - Part 1 Code on Gitlab

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies

Join our newsletter for expert tips and inspirational case studies