Open source has moved from being an important actor in software development to being central for plenty of people, especially thanks to Github. Most of us are simple users of OSS (Open-source software) but being brave and taking a step forward and becoming a contributor, or even an owner, could help you massively in different ways:

- Collaborating with clever people irrespective of their place of residence.

- Improve your social skills through remote communication. Being extrovert is only one of the ingredients for a successful engagement, OSS provides you with a comfortable and safe environment where you can explore other social skills.

- Giving back to the community.

- Great way of learning tools, languages or methodologies in a practical way.

However, being able to engage nicely with OSS could be hard. Let me share with you some tips than can help you to ease that experience:

Contributor's point of view

Find a project

That sounds silly, but sometimes, you don't even know where to start. The closer the project is to you, the easier it becomes to engage with. Enlisted in order of proximity:

- Talk with your colleagues. A lot of people are secretly working on exciting projects. You could really be surprised!

- Explore the tools that you use and love (or hate :) )

- Use some search tool: Github trending repositories, Open Hatch or Code Triage

Explore the project

Download the code, run the tests, use the tool, make a small change... Everybody has different ideas about what is nice code to work on, be sure that you want to spend your free time working on that codebase. You should be patient and understand that sometimes you will waste your time trying to figure out if that project works for you, no Readme or blog post can tell you if you'll enjoy working on the project.

By just doing that you could come up with things to work on for later, e.g.:

- Outdated documentation.

- Code that is hard to read.

- Flaky test suites or non tested areas.

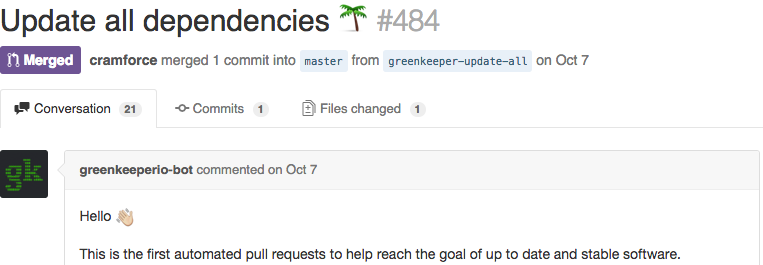

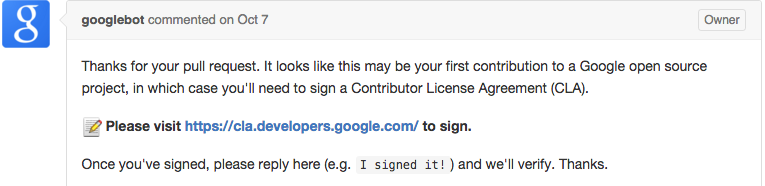

A project is not only its code, so you should explore its social side too. Chats, mailing lists, issues, pull requests, wikis... Imagine yourself applying to a company for a job and being able to spend as much time as you want reading most of their internals documents. You can do that with OSS, use that opportunity. You can even see bots talking to each other:

Be humble

Collaborating in OSS doesn't necessarily mean working on the Linux kernel. If it's your first time, be humble and grab something with a manageable essential complexity. Thanks to your previous exploration you should have enough information about that. Be aware of accidental complexity in general, that's a sign of laziness and in the long term, madness.

In the same way, don't start your engagement with the project doing a massive refactor or accomplishing some ambitious issue. You can make a difference by taking the time to familiarise yourself with the codebase before making any decision based on your strong judgements.

Believe in the project

As Rob Taylor pointed out to me the other day there are three elements to be motivated at work according to Daniel Pink: autonomy, mastery and purpose. If you don't believe in the OSS project you chose, you will lose a fair amount of purpose, so try to pick up something that really excites you. There are many fish in the sea, so feel free to move around and search for new projects if you're simply not having fun. That's the good stuff of OSS, for most of us it's not paying our bills so we can leave whenever we want.

Owner's point of view

Be accessible

Most of OSS's owners are looking for contributors. In order to attract the right people you need to provide the following:

-

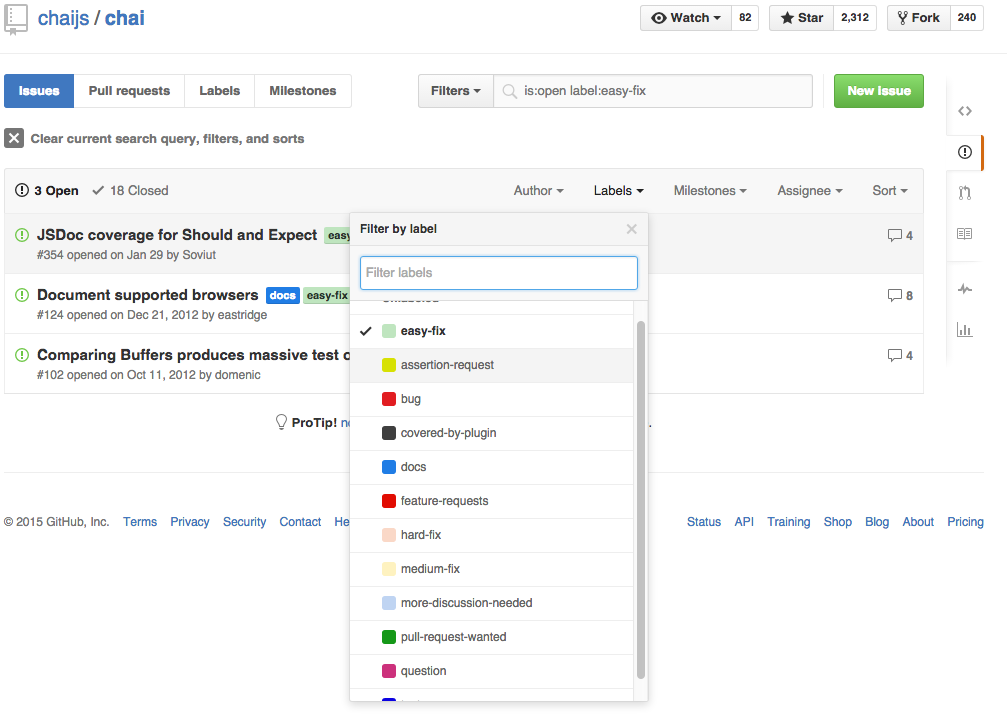

Clean entry points: not everybody has the same set of skills or the same interests. Organizing your issues around different categories is really helpful for the newbie.

-

Beginner friendly: As you can see in this repo, there are several beginner-friendly OSS projects.

-

Guidelines: it's really frustrating to invest a lot of time in a PR (Pull Request) and then getting a massive amount of feedback. You could think that your standards are universal, but even something like testing or clean code is not a shared value for everybody. The project should state clearly in the Readme or Wiki what are the expectations for a PR. Don't lower the bar, but explicitly state it. At the end of the day your project needs valuable code, it doesn't matter how much time the contributor needed in order to accomplish the task.

-

Communication tools: even if the project has great documentation you need to provide ways for the community to engage with each other. Gitter is a great tool for chatting and google groups are kind of ok for mailing lists. Be approachable there, it's useless to include a Gitter badge in your Readme if nobody is answering the questions.

Be clear

Most of the projects that I've found, lacked the right level of documentation (if you want a good example of the opposite have a look at ScalaTest. If you're developing a tool, provide living examples of different use cases. Asking to the new joiners to read tons of documentation could be not realistic, a live example could be the easiest way of explaining your project.

Don't scare people

Unless you want, of course :). Have a look at how Linus Torvalds handled some contribution into the Linux kernel. I can imagine that they have a project with more than needed volunteers and I understand that they have to be really careful about the quality of the code that they merge, but unless you want to scare most of the newbies, don't react like that to unpleasant code.

IN CONCLUSION

I've been really lucky in a way to get a chance to work with Marco Vermeulen, the creator of an awesome OSS tool called, SDKMAN. The first steps were really easy for me as the project was documented, the Cucumber BDD test suite was amazingly thorough and indeed, because of the availability of Marco. However, in the past, I've failed several times engaging with OSS projects and most of the times because of my mistakes. I hope that these tips will help to people that are thinking in collaborating with OSS. In the future I'll go into more detail about what I've learned working with SDKMAN.