This is part three of my talk, Design Patterns in the 21st Century.

The Adapter pattern bridges worlds. In one world, we have an interface for a concept; in another world, we have a different interface. These two interfaces serve different purposes, but sometimes we need to transfer things across. In a well-written universe, we can use adapters to make objects following one protocol adhere to the other.

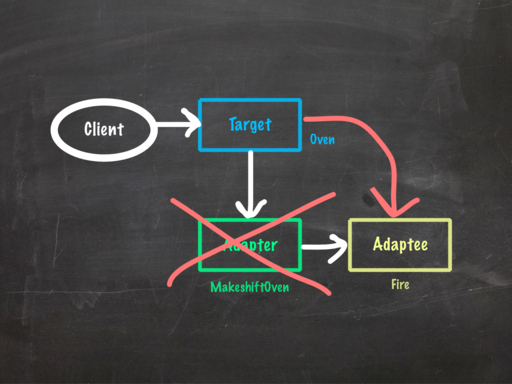

There are two kinds of Adapter pattern. We're not going to talk about this one:

interface Fire {

<T> Burnt<T> burn(T thing);

}

interface Oven {

Food cook(Food food);

}

class WoodFire implements Fire { ... }

class MakeshiftOven extends WoodFire implements Oven {

@Override public Food cook(Food food) {

Burnt<Food> noms = burn(food);

return noms.scrapeOffBurntBits();

}

}

This form, the class Adapter pattern, freaks me out, because extends gives me the heebie jeebies. Why is out of the scope of this essay; feel free to ask me any time and I'll gladly talk your ears (and probably your nose) off about it.

Instead, let's talk about the object Adapter pattern, which is generally considered far more useful and flexible in all regards.

Let's take a look at the same class, following this alternative:

class MakeshiftOven implements Oven {

private final Fire fire;

public MakeshiftOven(Fire fire) {

this.fire = fire;

}

@Override public Food cook(Food food) {

Burnt<Food> noms = fire.burn(food);

return noms.scrapeOffBurntBits();

}

}

And we'd use it like this:

Oven oven = new MakeshiftOven(fire);

Food bakedPie = oven.cook(pie);

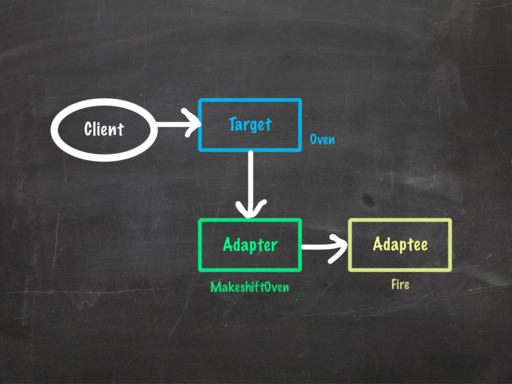

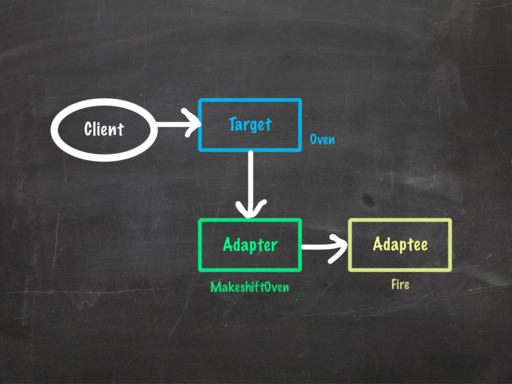

The pattern generally follows this simple structure:

That's nice, right?

Yes. Sort of. We can do better.

We already have a reference to a Fire, so constructing another object just to play with it seems a bit… overkill. And that object implements Oven. Which has a single abstract method. I'm seeing a trend here.

Instead, we can make a function that does the same thing.

Oven oven = food -> fire.burn(food).scrapeOffBurntBits();

Food bakedPie = oven.cook(pie);

We could go one further and compose method references, but it actually gets worse.

Function<Food, Burnt<Food>> burn = fire::burn;

Function<Food, Food> cook = burn.andThen(Burnt::scrapeOffBurntBits);

Oven oven = cook::apply;

Food bakedPie = oven.cook(pie);

This is because Java can't convert between functional interfaces implicitly, so we need to give it lots of hints about what each phase of the operation is. Lambdas, on the other hand, are implicitly coercible to any functional interface with the right types, and the compiler does a pretty good job of figuring out how to do it.

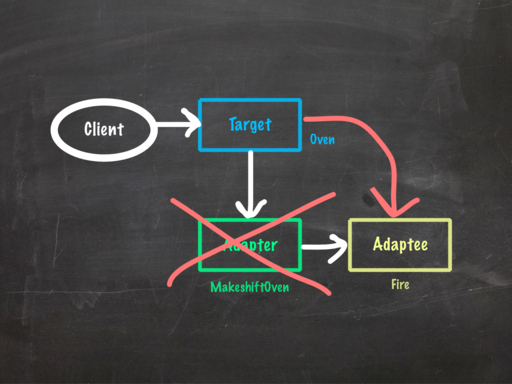

Our new UML diagram will look something like this:

Often, though, all we really need is a method reference. For example, take the Executor interface.

package java.util.concurrent;

public interface Executor {

void execute(Runnable command);

}

It consumes Runnable objects, and it's a very useful interface.

Now let's say we have one of those, and a bunch of Runnable tasks, held in a Stream.

Executor executor = ...;

Stream<Runnable> tasks = ...;

How do we execute all of them on our Executor?

This won't work:

tasks.forEach(executor);

It turns out the forEach method on Stream does take a consumer, but a very specific type:

public interface Stream<T> {

...

void forEach(Consumer<? super T> action);

...

}

A Consumer looks like this:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Consumer<T> {

void accept(T t);

...

}

At first glance, that doesn't look so helpful. But note that Consumer is a functional interface, so we can use lambdas to specify them really easily. That means that we can do this:

tasks.forEach(task -> executor.execute(task));

Which can be simplified further to this:

tasks.forEach(executor::execute);

Java 8 has made adapters so much simpler that I hesitate to call them a pattern any more. The concept is still very important; by explicitly creating adapters, we can keep these two worlds separate except at defined boundary points. The implementations, though? They're just functions.

Tomorrow, we'll be looking at the Chain of Responsibility pattern.

This post was cross-posted to my personal blog.